In the spring of 2014, residents across Flint in Michigan watched brown, foul-smelling water gush into their sinks. It was the start of what is now known as the Flint Water Crisis – one of the largest public health disasters in American history.

Many in Flint found the brown water not just unappealing. They felt it dangerous. Mothers reported children breaking out in rashes. Elderly residents complained of hair loss. Pets fell ill with their fur shedding in clumps.

When the people of Flint sought answers, they were repeatedly told and reassured the water was safe. But it wasn’t. And the worst thing about the Flint Water Crisis? It was preventable at almost every turn.

With the final lead water supply pipe reportedly removed from Flint over a decade later, we look back at what happened and why it cannot be forgotten.

Flint: A city in financial crisis and under state control

Flint’s troubles did not begin with water. Once a thriving hub of General Motors manufacturing, the city suffered decades of economic decline, population loss and shrinking tax revenues.

By 2011, Flint was drowning in debt. It was placed under the control of a state-appointed emergency manager. This role came with sweeping authority and powers to override local elected officials.

It was a shift which laid the groundwork for catastrophe. The emergency manager system prioritised fiscal authority over democratic input.

Decisions once made through community consultation now rested with a single official answering directly to the office of the governor.

In this environment, the idea to switch where Flint got its drinking water from emerged not from local residents or engineers with expertise. It came from cost-cutting spreadsheets.

The switch of water supplies to the Flint River

For decades, Flint had purchased treated water from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department. The water was clean, stable and safe. But it was also more expensive than officials wanted to pay.

In 2013, Flint announced it would join a new regional water authority. As a temporary measure whilst that project was being finalised, the city switched its supply from Detroit Water to the Flint River. A body of water long known by residents to be industrial and polluted.

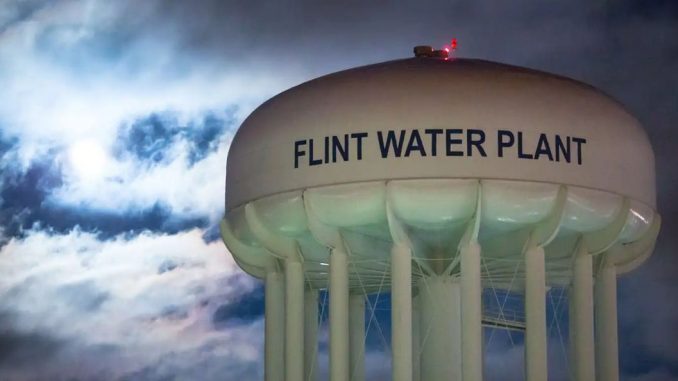

The switch took place on April 25th 2014. At the city’s water treatment plant, engineers began processing river water which was significantly more corrosive and therefore required advanced treatment.

Yet in the rush to save money, the plant skipped an essential step – adding corrosion control chemicals. The omission would become the single most catastrophic technical failure of the Flint Water Crisis.

Without corrosion control, this corrosive water began leaching lead from the ageing and leaking lead pipe network. An invisible toxin with no safe exposure level was now flowing directly into homes, schools and kitchens throughout Flint.

Early warning signs of the Flint Water Crisis… and official denials

Within weeks of the switch, complaints began pouring in. Tap water looked like tea. It tasted metallic. Skin was burning after showers. Children were developing mystery illnesses.

Every attempt to raise the alarm by residents was met with resistance. The state had one response: Relax.

At public meetings and press events, state officials insisted the water met all regulatory standards. These statements were later revealed to be misleading at best and deliberately deceptive at worst.

Residents were portrayed as overreacting. Yet when General Motors reported Flint River water was corroding engine parts, the company was quietly allowed to switch back to Detroit water. Residents were not afforded the same protection.

This stark contradiction raised a haunting question – if the water was not safe and causing damage to car parts, how could it be safe for human bodies?

The scientists who exposed the truth of the Flint Water Crisis

The turning point came not from government action but from independent investigation. Dr Moana Hanna-Attisha was a local paediatrician who began reviewing blood tests from Flint children.

She noticed clear patterns emerging. Blood-lead levels in children had doubled on average since the switch. In some areas, it had tripled.

When Dr Hanna-Attisha presented her findings at a press conference in September 2015, state officials publicly attacked her competence and accused her of causing “near hysteria”.

At the same time, water expert Marc Edwards and his Virginia Tech Team conducted an independent assessment of Flint’s drinking water.

Their tests revealed astronomically high lead levels. One home measured 13,000 parts per billion – far above the threshold for even hazardous waste.

The data from Dr Hanna-Attisha and the tests carried out by Virginia Tech combined formed an irrefutable body of proof. Within weeks, the state reversed its denials. The truth was no longer containable.

A secondary outbreak of Legionnaires disease

Unbeknownst to residents, a simultaneous crisis was unfolding. In the wake of the water switch, the region experienced a deadly outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease.

Legionnaires’ disease is a severe form of pneumonia linked to contaminated water systems. At least a dozen people died from it in Flint. Many more fell ill.

Internal emails revealed that some state and federal officials knew about the outbreak months earlier but had not informed the public. Families were left without answers as loved ones were hospitalised or passed away.

Accountability and the breakdown of public trust

Public outrage understandably escalated as investigations into the Flint Water Crisis uncovered a chain of government misjudgement.

Local officials lacked authority under state control. State agencies misinterpreted federal laws requiring corrosion control.

Federal regulators identified problems but delayed intervention. And the staffers at the governors’ office dismissed internal warnings.

Charges were eventually filed against several state employees and political appointees; although many cases were later dropped or stalled. For most residents, accountability remains incomplete.

The Flint Water Crisis is now widely seen as an example of environmental racism. A predominantly black, low-income city told its concerns about drinking water safety were imagined – even as they were being poisoned.

Aftermath of the Flint Water Crisis

A decade on from the Flint Water Crisis and most of the city’s lead service lines have been replaced. Water tests meet federal standards. But the human toll lingers.

Many families still distrust the public water network. They rely instead on bottled water. Parents worry about what unseen damaged have been done to their children’s long-term cognitive and behavioural health.

Despite the Flint Water Crisis being no fault of the residents, education and medical support programmes to help people recover remain underfunded.

On a national level, Flint sparked scrutiny of water infrastructure nationwide. Cities across the United States have since discovered their own lead pipe problems.

Whilst state officials are unlikely to start transporting highly corrosive river water through these networks, what happened in Flint was not an anomaly – it was a warning.

Lessons from the Flint Water Crisis

The Flint Water Crisis offers a series of painful but necessary lessons. Democracy matters. Removing local voices leads to dangerous decisions.

Science must guide policy. Officials firstly sought to cut costs by any means. They then ignored clear scientific evidence for months, instead choosing to accuse experts raising concerns as being hysterical.

Infrastructure investment cannot be ignored. Whether the ticking time bombs of PCCP pipelines installed during the 1970s and 1980s. Or the dangerous lead pipes rusting under the street of Flint which destroyed lives in a man-made disaster rivalling anything nature conjures up.

Finally, it goes without saying that clean water should be a fundamental human right. It is astonishing that the residents of Flint were first endangered and then had to fight for safe drinking water.

The story of the Flint Water Crisis is undoubtedly one of failure. But it is also a tale of resilience. Residents organised water drives, conducted testing and continually challenged officials.

They forced America to face an uncomfortable truth – environmental disasters are often human made. And they are always avoidable.

Leave a Reply